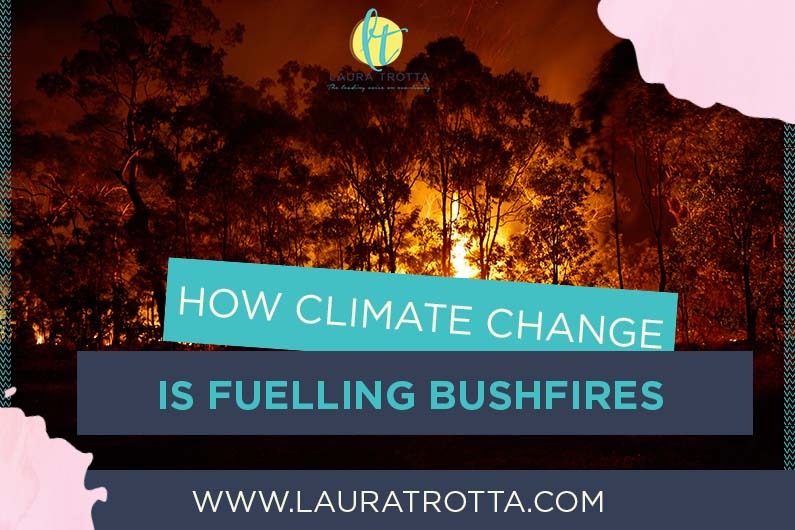

How Climate CHange is Fuelling Bushfires

The catastrophic and unprecedented 2019-2020 Australian bushfire season, colloquially referred to as the Black Summer, burnt an estimated 18.6 million hectares (46 million acres; 186,000 square kilometres, 72,000 square miles), destroyed over 5,900 buildings (including 2,779 homes) and killed at least 34 people (including a number of firefighters) (source). An estimated one billion animals were killed and some endangered species may have been pushed to extinction.

At its peak, air quality dropped to hazardous levels. Smoke from the Australian fires was detected some 11,000 kilometres (6,800 miles) away across the South Pacific Ocean in Chile and Argentina. The cost of the fires is expected to be in the billions of dollars.

While the fires that ravaged every state and territory in Australia, particular the south-eastern States, are now extinguished and the world’s attention has turned to fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, we cannot allow the Australian Black Summer to become a memory.

The impacts of Covid-19 will be a speedbump in contrast to the growing impacts of climate change.

It’s time to address the scary reality that the Australian Black Summer signals a new normal for bushfires in Australia and other regions around the world.

In this Episode of Eco Chat I’m joined by former Commissioner of Fire & Rescue NSW Greg Mullins to unpack the angriest summer of fires in Australia. We discuss how climate change is impacting the frequency and intensity of bushfires and how communities can reduce their bushfire risk in a warming world.

Podcast: Play In New Window

Subscribe in Apple Podcasts | Stitcher | Spotify

Australia has just experienced our worst fire season on record. Can you share what was so different about the 2019/2020 fire season from seasons in the past?

Greg:

This isn’t a flash in the pan. Together with other fire chiefs and emergency leaders for climate action and ex chiefs from every fire service in Australia and other emergency services, we saw this coming. We tried to warn the government. It’s not rocket science. Well, it is science. But unfortunately, in many countries around the world, including Australia, in the US, we have leaders who don’t tend to listen to the science and our fires in Sydney or New South Wales, and Queensland, to western states they started in July 2019.

Now, if you look back over the last 200 years, our fire seasons in New South Wales started in October and legislation reflected that. Over the last 20 years has been a real lengthening of the fire season. We have major fires starting to destroy property in August, the fires that started in July, that had been unheard of in the 20th century. But in the 21st century, it’s now become a regular thing.

We had the most extreme fire weather ever experienced in Australia on multiple days. So in the past, when we had major property losses, there were normally one or two days of extreme weather. And then that was it. You’d have fires through the summer, and then there’d be one really bad day and that’s when you lost all your properties. In the 2019/2020 season we lost hundreds of properties on multiple days. We had more days of very high, sever, extreme and catastrophic fire danger than ever before. We broke temperature records, we broke dryness records, the driest year on record the hottest year on record and incredible wind speeds and velocities.

So it was just primed for disaster. That’s exactly what we experienced.

And look, I was even I was shocked by the enormity of it, we lost 10 times more homes than we’ve ever lost before we lost 33 lives. A number of those were fellow firefighters. I got into some sticky situations myself out on the front line. I’m not as young as I used to be and one night in particular I thought I might end up in hospital or worse, but I got through that. And it was really frightening. I think you know, Laura, I was in California in November at the Kincaid fire. I’m talking to people from Cal Fire and I’ve worked out there over the years and studied at the US Fire Academy. And they’re seeing exactly the same trend. Back in 2018 the city of Paradise was basically destroyed. 20,000 homes destroyed, nearly 100 dead. The year before 9000 homes destroyed.

So climate change is supercharging the fire problem worldwide. England’s getting fires. They never used to get bushfires. Greenland, wet rainforests are burning in places where they’ve never burnt before. This is climate change. We need to get used to it and we need to do something about it. No matter what Prime Minister Morrison or President Trump or other people say, it’s real, we have to get on with the job of reducing emissions.

How is climate change driving an increase in the frequency and intensity of bushfires?

Greg:

Look, this might get a bit detailed, so pull me up if I’m getting boring. But the basic thing is that it’s getting hotter. So in the last hundred years in Australia, 120 years, it’s gone up a bit over one degree on average. But what the averages mask is the extremes. We had our first just about 50 degree day in Sydney, 50 degrees Celsius, around 118 degrees Fahrenheit. This punishing day of heat but they’re happening regularly. So it’s driving heat waves. So the extremes are more extreme in terms of temperature. It’s changed the rainfall patterns. So winter rainfall in southeastern Australia, which is one of the most fire prone parts of the planet, is 15% reduction. Now May to July… now I remember as a kid going on the May school holidays, and we went camping every year and I’ve don’t know why because we always got rained out. But it doesn’t rain anymore. So it’s a beautiful 24°C May sunny day today and it’s forecast for 27°C on Friday.

It should be 10 degrees cooler.

When I was a kid, it would be 10 degrees cooler, this is getting into winter. So what that does, that lack of winter rainfall that allowed us to carry out control burning in the so called cooler months, which are now warmer. It’s getting too dry to do that burning. The fires are getting away from us. And then the fire season as soon as we get on the East Coast westerly winds come off the desert from July and because there’s that moisture there or there used to be 20 years ago. The fires don’t run much, so they’re easily controlled, but not anymore. It’s tinder dry and the fire start to run, they get bigger and bigger if they start in remote areas from lightning strikes, which we’re getting more of. And by the time the temperature goes up, we’re in real problems, we’ve got real problems. So that’s happening every year. Now, the fire seasons as I said are much longer. Now what that does. In Australia, they used to start in the north, migrate south, the weather conditions, and it was a passage of high pressure systems across the continent.

Now because it’s warmer, we’re getting overlapping fire season so we can’t share fire trucks, aircraft and firefighters like we used to. And that used to be the basic paradigm, but the basic doctrine of fire services in Australia we’ll be okay because we’ll be able to bring in interstate assistance. Well, not anymore and this year every State was burning at the same time, so they had to call their firefighters home. So we needed about 1000 firefighters from Canada, the US, US Zealand, even places like New Guinea, Malaysia, and France. We had massive international assistance that has never happened before. And that’s because of climate change changing when Australia burns. It’s also affecting our large firefighting equipment, large firefighting aircraft. They all come from Canada and the US. We lease them. But because their fire seasons are becoming much longer, they can’t release them in July and August and September and even October when we need them. So we’ve got to look at do we buy our own? The New South Wales Government bought itself a 737 15,000 L air tanker because of the previous years’ experience (2018) where we were losing homes in August, which was unprecedented.

Not every year is a bad year. When I was a kid, my father used to tell me about the cycles, local cycles, 10 years, 10 years, 21 years that seemed to happen, looking at weather patterns. And that’s when you get the bad seasons. Now the Blue Mountains west of Sydney, again, one of the most fire prone parts of the world where lots of properties and lives have been lost over the years. If you look back through history, there were fires in 1926, 1939, 1944 (my father fought those fires – that was a bit of a blip on the radar). Actually the 1939 fires didn’t really go through the mountains so it was 1936, 1944, 1957, 1968, 1977, 1994 and then 2001/02, 2007, 2013 and now 2019/20. So they’ve gone from every 10 to 13 years to every six years.

So we’re getting more fires, they’re far more destructive. And one of the biggest things that I’ve noticed is my dad talked about the 1939 bushfires and lightning coming out of the smoke clouds and starting new fires. And what he was describing was pyro-convective activity, so a bushfire making its own weather. So the convection columns going up because of unstable atmosphere, moisture condensing forming cumulonimbus clouds, storm clouds. Pyro meaning fire. Pyro cumulonimbus.

There were about two instances of that recorded between 1973 and 2001. Since then, dozens and this year probably 30 or more, just in this season 30 or more. On those days when those fire storms started, and I was in the field during one of them, the winds come from every direction. You get downdrafts, updrafts, and lightning starts near fires, spotting. So burning branches being carried up in the conviction column, and then deposited in unburnt bush, 8 to 12 kilometers ahead on some days. And you can’t fight fires like that. On one day, one of those storms picked up an eight tonne five track and deposited it on its roof and killed one firefighter and injured the others. So you can’t fight fires in these conditions. This is all new. I’ve read all of the science naturally. It’s all explained, and it was all predicted. And frankly, humans can’t do anything when Mother Nature gets angry.

What is it about Australian conditions that makes our fires the most ferocious in the world?

Greg:

Australia shares a lot of problems with California and when I first went there in 1995 they pointed out to me, they’re very grateful. They said “Look at all those trees” and I said “Oh yeah, gum trees!” They said, “Yeah, thanks for them. They’re not native. They came here from Australia and we hate them. They’ve really made our bushfire problems worse.”

But, look, Australia is an enormous country. We’ve got many different geographies, vegetation types, but one of the emblematic species of course is eucalyptus trees. There’s so many different types of those. They are full of oil, the leaves are full of oil, and they drop bark, dry twigs, which contributes to what we call fuel loads. But underneath that you’ve got native grasses, shrub layer, and they’re all, depending where in Australia because it’s different… we go from tropics to temperate to Tasmania with Highlands and wet rainforests. Eucalyptus are very adapted to very, very dry conditions. So there’s not a lot of fuel moisture, and the types of leaves, needle leaves and things made to conserve moisture. They also dry out very quickly in the sun, in the hot summers when the relative humidity gets very low, it sucks the moisture out of that vegetation. And when you’ve got a layer of dead leaves, twigs, and bark on the ground, which can be up to 30 tonnes to the hectare or more, you have major problems and all that shrub layer will go. And then the tree crowns, those leaves that are full of eucalyptus oil, you’ll see that black smoke, just like a big factory is on fire. That’s the oil in those leaves burning all those hydrocarbons. So it’s primed to burn and it’s always burnt.

The carbon record goes back millions of years. Indigenous people managed the landscape really effectively using fire for 60 – 70,000 years. When Europeans arrived, we decided fire was bad. Let’s stop that, so that fuel problems became even worse. Now, we try to manage the fuel loads by hazard production burning and fire breaks. Look, frankly, with the extremes we’re getting in weather now, what it showed, the spotting eight to 10 kilometers or 100 meter wide or 50 meter wide fire break isn’t going to withstand an ember attack. Which some of you might have seen on TV, just incredible. Loads of sparks getting into every little crevice in the building setting everything alight for kilometers. So it is constructed to burn.

The other thing is we’ve got some very rough geography, the Blue Mountains, very steep Gippsland in Eastern Victoria, the Great Dividing Range. Fires burn faster up hill. Heat goes up. So the steeper the slope, the faster the fires go. So we have this thing of fires just racing up a hill, spotting to the next mountain top and it can spot for kilometres. I saw it in 1977, 16th of December 1977, I’ll never forget that because I nearly lost my life. Because a fire burnt over the top of us. I looked to the east and every mountain top for as far as I could see was on fire and then the fires in the middle, raced up the hillsides and met the other fires and off they went.

So, look, it’s always been bad. California is a bit different. There’s a lot of brush and grasslands. They’ve now got the problem with climate change of less snowpack, so it doesn’t kill the bark beetles in the some of the native species over there. So the bark beetles are killing the trees so leaves and branches are dropping and creating an incredible increase in fuel loads and dry, dead fuel directly related to climate change. So it’s a combination of all those factors, geography, vegetation, but this summer last summer, we had wet rainforest burning, and buildings lost in those rainforests where they’ve never had fires before.

I talked about the Blue Mountains and the frequency of fire seasons. But Tasmania where it’s quite cool, used to be quite wet, the rainfall patterns have shifted. Veteran firefighters don’t recall lightning starting fires in Tasmania until the last decade. But in 2016 thousands of lightning strikes occurred in the world heritage alpine areas that used to be too wet to burn. And in 2018 the same thing happened. Now, their frequency of bad fire seasons was basically about 50 years apart. Thirty to 50 years apart. Now it’s about every five years, and they get bad fires. So that’s over the last two decades. So that just really shows how things are getting worse and worse.

Where do our current bushfire management practices need to change and adapt to take into account increased risk from climate change?

Greg:

Great question! If you find anyone in the world who has the answer, please put them in touch with me, because I don’t think anyone does. And I point to California, I have been quite a number of times over the years. And I call that firefighter heaven. Because you have as many fire engines, as many firefighting aircraft or firefighters as you need. You just click your fingers and they’re there.

The resource level is incredible, because they’ve got a big population base and it’s dispersed through the hazard area so you can pull out a lot of resources. Now they can’t cope, so in Australia with our huge distances, and the sheer logistics of getting firefighting assistance to remote areas. Like New Year’s Eve, I travelled from Sydney for five hours. I left at 5am to go to Batemans Bay on the south coast and they lost 700 homes that morning but by the time we got there at 10am homes were burning and there were pyro-convective storms and people were losing their lives. It was just outrageous.

In the past when I was a young firefighter, it was all about what they call the wet stuff on the red stuff. So just putting out fires. In the 1960s, they started to do a lot more controlled burning, to try and reduce fuel loads. And that was after fire disasters in Western Australia wiped out the town of Balingup up, so they used prescribed fire. It’s interesting over the years watching the different stages Ash Wednesday in 1983, in Victoria 2000 homes and 72 lives lost I think it was.

We realized after 1983 that we needed building standards, we needed better command and control systems and which again, we stole from the US the command and control system. And so that’s why we can interoperate very easily because we use the same systems, but it was just an evolution of taking different measures after 2009. 2000 homes lost and 173 lives lost in Victoria on Black Saturday. It was all about warnings and getting information to the public.

So in the future, we’re going to need to integrate all of those things and more. Fire bunkers and refuges, even planning standards. Look, this area is too fire prone, no one can build there anymore. We’re not going to rebuild but governments will have to buy up the land and move people away to safer areas.

There’s so many things to do. But my message and that of other five Chiefs, not only here but around the world is talk all you like about adaptation and mitigation. The horse has bolted. We can’t cope. There’s no fire service in the world that can cope with what’s going on. It’s going to take integrated measures.

This is the cost of climate inaction.

It’s a bit like if you’ve got a pot of water boiling on the stove and it starts to boil over. What do you do? You don’t just keep mopping up the water that’s overflowing, you actually turn the stove off. That’s what we need governments worldwide to do. It’s getting too hot. It’s driving disasters. They need to dial the heat down. It’s going to take a while but the only way they can do that is credible real actions on emissions reduction.

Commit to net zero as quickly as possible. Invest in new technologies. And I think Australia can be a powerhouse. Ross Garnaut says we can be a powerhouse with green technologies and renewables. That’s what we need to do for the sake of our kids and our grandkids. I can’t imagine what sort of world they’re going to face, because we’re just on the bottom rung of the ladder that’s started to shift upwards at a very fast rate. What we just experienced. I hate to say it, but it’s the new normal. Well it’s not really, because it’s going to get worse.

Laura:

The 2019/2000 bushfires happened during the peak summer holiday period for Australians. We traditionally go to the beach or to the mountains or wherever for that time of year to relax and have fun. One of my girlfriend said to me “Is this the end of summer holidays? Like, is everyone going to start taking their main holiday around Easter now or in winter because the summer is too dangerous.”

And we don’t have enough facemasks in Australia for the pandemic because so many were used by people to be able to breathe easier in Melbourne and Sydney over this summer from bushfires. And summer sports were impacted. We were at the Adelaide Oval to watch a Big Bash cricket match, which was delayed because of smoke. It’s the new normal. Obviously safety is number one and the lives, livelihoods and houses. But it’s just going to infiltrate and affect everyone’s life and enjoyment and pleasures as we know them, isn’t it?

Greg:

Thirty three people lost their lives directly to the fires. A very in-depth, recent epidemiological study estimates that 417 people lost their lives from smoke, just from smoke on the east coast. And so you’re talking 450 deaths from these fires, there were probably far more. One of the authors of that paper said that we didn’t really go as deep as we could we think there’s probably a lot more, so hundreds of people lost their lives from these fires.

I was reading The Sydney Morning Herald this week and an international paper with international collaboration between the number of universities around the world. They’re saying that in 50 years, there’ll be big parts of the planet, maybe a third of the population will be facing conditions like the Sahara Desert, and the temperatures will be too high to survive. So they’ll have to be massive shifts, the populations.

I know not a very cheerful person to speak too. Maybe through disaster, people will wake up and demand, via the ballot box, action. So if their government’s are not acting on climate change and emissions on behalf of our children and our grandchildren, vote them out. And I don’t really care what flavour of politics you go for, if they’re not doing the right thing, we need to vote them out. The power is in our hands.

Laura:

I know you say that you’re not the most fun person to talk with, but the truth is really important. And it’s so important right now in terms of climate change and all the impacts of climate change like increasing pandemics, not just bushfires. But of course, you’re the bushfire expert, I’m going to ask you to put that black hat on right now. You know, the black hard hat on, if you like, and in your worst nightmares what do you think is going to happen? What will these bushfires look like in 10, 20, even 50 years into the future if we don’t adapt quick enough?

How will bushfires look 10, 20, 50+ years into the future if we don’t adapt?

So first thing, we can’t adapt. There’s too much to be done, and it’s been left too late. So the only thing we can do again, is to try to dial down the heat. A lot of heating is locked in because of what we’ve emitted and continue to emit. So things will get worse before they get better. But we can turn it around. And you have to have that positive view. Yes, we can turn it around.

If we don’t?

Say the Paris talks were aimed at 1.5 degrees. Well, that’s gone, because nobody did anything. So let’s say two. You speak to climate scientists, they say we’re actually tracking 3.5 to 4 degrees warming if we don’t do anything. Then it’s probably a planet that’s not survivable, except in a few small areas.

Then the number of extinctions of animals that are happening around the world. In these fires I saw things I’ve never seen before. I saw stuff I never thought I’d see and it still keeps me awake at night. Growing up, animals knew where they could go for refuge and get away from fires. And that was impossible during these fires, they couldn’t get away. Massive areas burnt, no refuges.

If they survived they were probably injured, they probably starved. Or there was predation by pests like foxes, cats, dogs. So a billion animals were killed at least – that’s the University of Sydney’s estimation.

We’re just looking at worse and I think we can’t sugar coat it. We’ve got to look at it and say “this is like being on a war footing.” And we need our governments to do more.

I was really heartened actually by the COVID-19 response because the Australian government and State and Territory governments listened to experts. They listened to the science and acted. If only they’d do that on climate change. And if only they had done that on bushfires during the last bushfire season.

Now, I’ll rule a line under that, because what’s done is done and I did a lot of comment on the Australian government’s response to the bushfires, which was too little too late and was driven by media, but I think they learned from that. And I, you know, I give them a big tick for the COVID-19 response. So we’re not facing what other countries are facing – we’ll be able to start gradually, opening things up soon because of those early measures, early strict measures. We’ve got to move on.

Hopefully, as we recover from COVID, governments will have smarts and they’ll invest in green technologies and a new way of doing business so we can reset. Yeah, so look, I don’t want to really think about or talk about what the bushfire problem could be in five years, let alone 10 years, or 20, or 30, or 40, or 50. I want to think about a world where governments finally say, yes, this is real, this is urgent, we need to be on a war footing, we’re going to drive down emissions to stop those horror scenarios from actually occurring.

What are some ways you believe communities can reduce their bushfire risk in a warming world?

Greg:

Look, the big thing is, again, I get back to the big picture. They need to demand action on climate from local government, state government, federal government, and use their votes and use their voices. So that’s the big picture.

But if they’re able to join their Volunteer Fire Brigade, their local volunteer fire brigade, because that’s where they’ll get the best information, current information about risks, and how to reduce those risks. Really, I’m always amazed and even this fire season, everyone saw it coming, and I’d go to people’s places and yes, put my life on the line. One night in particular, where I thought I might lose it because people have done nothing to manage the risks on their patch of land, and then they blamed the National Park. But if they’d actually kept the fuel levels down on their block, the fires wouldn’t have got anywhere near their home. There would have been a bit of ember attack, and if they had sprinklers and hoses, they would have been able to manage that. But people can’t cop out and expect the government to do things for them. They need to take action every year before spring now, not summer, because our fire season starts in spring.

Look at your defensible space. So have you got space all around your house where firefighters can get in, dragging hose lines and be safe while they stop the ember storm setting fire to your house. If the answer’s no – if flames can reach your home from your beautiful bush garden or beautiful long grass down the back then you’ve let yourself down. And if you need help there are programs to get help from local councils and the fire services.

Look at modifying your homes and look at Australian Standard 3959: Building in Bushfire Prone Areas and some of the measures there like boxing in eaves. Look at your gutters, stopping leaves getting in your gutters. Any penetrations in your roof where embers can get in. And on the worst days, outdoor furniture, anything that will catch fire like woodpiles, get them away from your house. And I think the biggest thing that we learnt from 2009 as fire services was primacy of life. If you hear that there’s going to be catastrophic fire danger, leave the night before. Don’t wait because you might not survive.

You’ve witnessed the growing frequency and intensity of fires over a 50 year period. If you had the full attention of the Australian parliament for a session, what would you request of them?

Greg:

I’d explain, just in firefighting terms what it means. What the warming climate means and I’d keep it simple. I would talk to them about my grandchildren, and what my hopes are for their future. But what I’m actually seeing which is really grim, and that it’s in their hands to make policy decisions that will reduce emissions, will bring down the temperature so that future generations have a fighting chance and I really believe that if you have smart people doing smart things, that policy sense, businesses will rise up to the challenge, and it will help our economy.

We’ve got wind, lots of sun, abundant resources for making batteries, lithium and other deposits. We can be a powerhouse. We really should be a powerhouse of green technologies supplying the world. It can be a new boom for Australia and be good for all of us. And underpinning all that, as a firefighter, I’d say you need to give far more resources to the men and women on the front line who are putting their lives on the line for us day in day out.

About Greg Mullins

Greg Mullins is an internationally recognised expert in responding to major bushfires and natural disasters and developed a keen interest in the linkages between climate change and extreme weather events over almost 50 years of fighting fires. He coordinated responses to many major natural disasters over more than 2 decades, retired as Commissioner of Fire & Rescue NSW in January 2017, then re-joined the volunteer bushfire brigade where he had started in 1972. During the 2019/20 bushfire emergency he fought fires throughout NSW.

During his 39 year career he served as President, Vice President and Board Chair of the Australasian Fire & Emergency Service Authorities’ Council, Deputy Chair of the NSW State Emergency Management Committee, Australian Director of the International Fire Chiefs Association of Asia, NSW representative on the Australian Emergency Management Committee, Australian representative on the UN’s International Search & Rescue Advisory Committee, and as a member of the NSW Bushfire Coordinating Committee. He is currently Chair of the NSW Ambulance Service Advisory Board.

In 2004 he was invited to address the International Fire Science Conference in Ireland on the impacts of climate change on emergency services and has spoken at international conferences in the UK and Singapore about bushfires. As acting Chair of the NSW State Emergency Management Committee in 2005-6 he re-established a Climate Change Working Group focussed on adaptation and was a member of the NSW Government’s Climate Change Council from 2007-16.

He worked with bushfire fighting authorities in the USA, Canada, France and Spain during a Churchill Fellowship in 1995, studied at the US National Fire Academy in 2001-02, and represented Australian emergency services at many international forums. In November 2019 he attended the Kincade fire in California as an observer then returned home to fight fires in Australia.

- Sustainable Home Design- factors to consider to maximise sustainability - July 28, 2022

- Advantage and Disadvantages of Tiny Houses - May 31, 2022

- How School Strike 4 Climate is Empowering Youth to Fight for Their Future - May 1, 2022

Laura Trotta is one of Australia’s leading home sustainability experts. She has a Bachelor of Environmental Engineering, a Masters of Science (in Environmental Chemistry) and spent 11 years working as an environmental professional before creating her first online eco business, Sustainababy, in 2009. She has won numerous regional and national awards for her fresh and inspiring take on living an ‘ecoceptional’ life (including most recently winning the Brand South Australia Flinders University Education Award (2015) for the north-west region in SA and silver in the Eco-friendly category of the 2015 Ausmumpreneur Awards). With a regular segment on ABC Radio and with her work featured in publications like Nurture Parenting and My Child Magazine, Laura is an eco thought leader who’s not afraid to challenge the status quo. A passionate believer in addressing the small things to achieve big change, and protecting the planet in practical ways, Laura lives with her husband and two sons in outback South Australia.

Laura Trotta is one of Australia’s leading home sustainability experts. She has a Bachelor of Environmental Engineering, a Masters of Science (in Environmental Chemistry) and spent 11 years working as an environmental professional before creating her first online eco business, Sustainababy, in 2009. She has won numerous regional and national awards for her fresh and inspiring take on living an ‘ecoceptional’ life (including most recently winning the Brand South Australia Flinders University Education Award (2015) for the north-west region in SA and silver in the Eco-friendly category of the 2015 Ausmumpreneur Awards). With a regular segment on ABC Radio and with her work featured in publications like Nurture Parenting and My Child Magazine, Laura is an eco thought leader who’s not afraid to challenge the status quo. A passionate believer in addressing the small things to achieve big change, and protecting the planet in practical ways, Laura lives with her husband and two sons in outback South Australia.