Are you ready to inspire the conscious kids in your life to save the world?

If you are it’s time you met Captain Garbology, aka Lee Constable.

Lee Constable is a presenter, producer and, most recently, children’s book author with a focus on science, technology and society. As the host of Australian science TV show, Scope, she researches, writes, presents and produces segments on diverse STEM topics.

Put simply, Lee is a scientific artist, or a creative scientist!

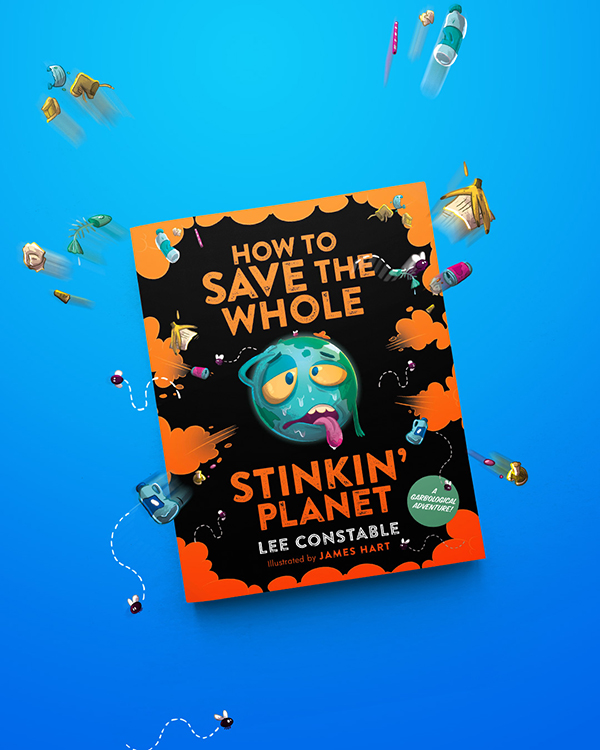

Lee’s new book How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet takes young readers (grade 2-6) on a garbological adventure. A superhero called Captain Garbology takes conscious kids on a quest to become Waste Warriors with hands-on DIY activities, waste science 101 and fun quizzes!

You can purchase How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet HERE.

Podcast: Play In New Window

Subscribe in iTunes (also on Spotify)

How did you go from a girl growing up in country NSW to being a presenter, producer and children’s book author with a focus on science, technology and society?

LEE:

I don’t even know. Well I do know because I was there the whole time, but I don’t think there’s any one path into TV presenting or media or whatever it is. And so my path was I was brought up on a sheep farm in New South Wales where my parents are still farming to this day and I don’t think there’s any end in their farming days in sight.

LAURA:

The drought hasn’t got them?

LEE:

I think most of my childhood really feels like it was drought. When I was a toddler through to kindergarten, around 1994/95 we had droughts and then we had the big one through my teenage years which was at the time the biggest drought. So yeah, I feel like drought and maybe that explains why a lot of my generation hasn’t stuck around on the farm sadly, but also that link between humans and environment, environment and humans like was always made really clear to me and with my family and their interest in farming came hand in hand there, they’re caring for the environment, so yeah, that’s definitely where it started as far as like being interested in science and environment itself.

So I also was, my sister and I actually were both really into drama. We love theatre. And when it came to choosing what to do at Uni, I decided to do a double degree because I really wanted to do theatre. I really wanted to do drama, but I also wanted to do science, particularly environmental science because I thought maybe become a climate scientist and finally solve this climate change problem. But the longer I went into uni, the more I realised that actually that’s not really where the solution necessarily had to come from because we already knew so much about how to solve the problem, what the problem was, but became more of a communication issue, I guess for me is what came out of that. So yeah, apart from drama I was also studying sociology, so really looking at humans and society. So I started off thinking arts and science are very separate things and I should leave them in those separate baskets but by the end I could say all of this come together.

And then during my honours year in science I realised that I really wanted to get into science communication. So that’s where I went. I went into science communication, science media. It was during my honours actually that I hadn’t really voted that much and in looking into how different parties were acting or not acting on climate or denying climate change even, things like that all became apparent to me in that early stage of my career, I guess. Yeah and it all fed into as well me wanting to get into science media and science communication because there’s a huge gap between the scientists and even the media let alone the media and the public and scientists and politicians etc. So that’s really where I brought it all together and one thing led to another and I joined the science circus and travelled remote and regional Australia doing live science shows for schools and community groups and I got a job at the National Botanic Gardens doing night time tours with spotlights for kids. I got a job at the ACT government in waste and recycling comms in education, so I was giving tours of the landfill and recycling sorting facility to community groups and school groups yet. And I just love that aspect of being able to connect the dots with people and talk face to face and bring in some of the theatrics even in the live science shows and things like that.

So I happened to get shortlisted for another TV presenting role with totally Wild at the time that the previous host, Dr. Rob who was the host of Scope, the science show that I host now was moving on after 11 years, the entirety of the show’s existence being the host and they saw my science presenting experience and offered me, well a shot initially to do a screen test and things like that, but then offered me the gig so, yeah, I’m very fortunate. So it was right time, right place, right person because you can put in all those hard yards to make yourself the right person for something. But then again, if you don’t do all those hard yards to make yourself the right person, it won’t matter. Yeah, that’s my story in short.

you refer to yourself as a science communicator. Can you explain what that is exactly and it’s so needed today?

LEE:

Science communicator I think when people first hear the term, if there was a stereotype of science communicator, I think it would be more of in the science education, science outreach, people talking to public about science, but it’s actually really broad. So science communication is a huge umbrella term and under it you have science and the following or the followings application to science, which is everything from media in journalism, entertainment, outreach, events. You have policy and politics also psychology, marketing, communication as a whole as well as teaching pedagogy, any number of things, art, visual art, music, all those things. So really when you want to break down what type of science communication you’re doing within that, it all depends of course on your audience, your purpose, your topic, what you want them to take away from it.

And there are so many valid reasons to do science communication as well. I think the thing that comes to mind often to people is science communication is for us to educate the public on these science facts. That’s just one valid way to measure science communication. Another valid reason to do science communication is to entertain or to bring about a trust for scientists themselves, to break down stereotypes of who is a scientist or encourage people into science careers, maybe to influence the way people vote. They may not understand all the science facts, but they might have a good appreciation for scientists or trust in what scientists do. So there are so many different measures of successful sci comm that all is very much a case by case basis. And I think one of the down falls sometimes in the field is that even those people within the field can sometimes be too quick to judge the value of certain sci comm based on assumptions that they’ve made rather than what the actual aim of the sci-commer was. So yeah, there’s a lot to take into account.

LAURA:

Wow. That is probably the best summary of science communication I have ever heard, Lee. I don’t think you missed a beat. I mean, of course podcasting, that’s another science comm, isn’t it?

LEE:

Yeah, absolutely. Any type of media for any audience. And really it’s not a pure field. It can’t be a pure field. It’s the application of many fields to science. And sci comm can even be about effectively communicating science from a scientist whose an expert in a field to another scientist who’s a potential collaborator but in a different field. It could be communicating your science as a scientist, but you want to commercialise it, so communicating it to the business world. So it doesn’t even need to be the broad public audience sort of a public audience using inverted comments. Yeah, it’s a lot more broad than that and it can be a lot more internal than that within an organisation even.

LAURA:

I’m just trying to think of other examples of science community. I’m sure, would they even be science cartoonists? Have you come across them?

LEE:

Oh yes, absolutely. One time when I was podcasting actually, I interviewed a science cartoonist or science graphic novelist as well, Stewart McMillan, M-C-M-I-double L-N. He’s got graphic novels that tend to draw from themes of science through history and there’s one that draws on climate change. He doesn’t have a science background, but he likes to use his art to talk about science related topics.

how important are the arts to science and science is to the arts?

LEE:

Yeah, I think that it’s so important it. We’ve changed the way we look at things. No one ever said to DaVinci that he should choose art or science. It was kind of just you’re a polymath. You’re someone who is inventive and thinks outside the box and applies that to many things. But also I think like when we talking arts, we’re not just talking creative arts and creative writing and visual art and music and dance and things like that, but also humanities, social sciences. And I think there’s a lot that all of those fields that I’ll call the arts have to offer science because quite often the way that science as a system or a sector is structured means that the focus is on the paper and the outcome and the research, well outcome being research, published research and grants and you know the wheel goes on.

But beyond that I guess then there’s sometimes a frustration from the science community when their science is not being taken up by society. So I think it’d be awesome if we could see scientists and ethicists and social scientists work hand in hand from the conception of an idea for research to completion and then implication and communication because often we’re on the back foot as communicators. The science is already done by the time we were writing the press release and then talking about it to the public. And then you get a lot of miscommunication potentially. You get potentially science that has been created without the end user necessarily in mind or without certain social implications in mind either when the research is being done or in the way it’s being applied. So I think that science could benefit greatly from what arts and humanities have to offer in that regard.

In my own fields, a lot of it’s to do with entertainment and performance and yes primarily I do want to entertain people with science because I want them to enjoy themselves and I want them to have a positive association with science. Whether or not they memorise every single fact or piece of information that I present on the show is not really as important to me as someone watching it, a kid watching it and thinking science is cool, science is fun or I didn’t know there was science in tractors, but here we are. So that’s what arts can offer to science I guess, because that then leads to maybe that kid will become a scientist, but even if they don’t, potentially they’ll have a positive view of science. Potentially they’ll be open to seeing scientists as trustworthy people and listening to their recommendations on something like vaccination or climate change that we see become a controversial topic.

When it comes to what science can offer the arts, I’m going to be controversial and say, I actually think the arts can offer more to science at this stage than the other way around. And I honestly think that’s because of some of the academic arrogance that you see in science that actually prevents scientists from really seeing the value in other fields which is a shame. And I can’t generalise, obviously I know lots of amazing scientists who don’t have that academic arrogance, but I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t an issue in a lot of areas of the science sector. So yeah, I think science and arts have a lot to offer each other, but I do think science needs to be more open to the arts than it currently is as a sector.

LAURA:

Yeah, thanks for your thoughts there, that’s an interesting one to think about. I think science can offer art content or ideas that the artists can then just run away with and create something truly amazing.

LEE:

Absolutely. And definitely there’s a lot of crossover between science and arts in different ways. Thinking creatively, walking a path no one has before in your own field. And I think a lot of artists like to use science as their subject matter because they do find it interesting because they do see the wider implications that science has on society and they want to study that through their own lens. So yeah, I definitely say that as, you’re right, something that the sciences offer arts.

Why did you write “How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet”?

LEE:

Why did I write it? Well, I think you’d have to be asleep if you didn’t realise how big climate change has become as far as what young people care about. We tend to stereotype young people and what they care about as these frivolous things, but world wide, we’ve seen this huge movement of kids unable to vote, unable to make maybe household decisions about what they buy or their energy or whatever. But as a united front saying we care about the planet. You need to do something for the planet. You leaders need to step up because it’s our future. So partly it’s because I see that and I want to help nurture that maybe in kids who don’t know where to start, and also provide a resource for teachers and parents to talk with kids and have fun with kids while learning about sustainability.

So I really wanted to make something that wasn’t just about climate change itself, but was about something practical and concrete that’s a starting point which is waste in this case and garbage, that’s a starting point for parents, teachers, librarians and kids to learn together and open up a discussion about our everyday actions and the planet and what the links are between those two. And then go through the various different ways that we can make decisions. And we don’t even remember when we first put something in the bin. It’s not really a milestone in our lives that we remember or a responsibility we remember stepping up to the mark of when we were a toddler or whatever. Sometimes you get your baby to drop something for you in the bin, but it really, it is such an everyday activity that it just helps you or a kid or anyone be mindful in that moment when you’re holding that piece of rubbish about what it’s made from and where it’s going next. So no, I don’t think recycling alone can save the whole stinking planet. But I do think that thinking about waste and recycling is a really good concrete every day actionable place to start for kids and educators when it comes to talking about the relationship between us and the planet and what stinks.

LAURA:

Yeah, no, I think it’s brilliant and kids just get it. I mean, I’ve got two boys as you know, a nine year old and a seven year old and one of their jobs is to take out the recycling which they do. We’ve got quite a large recycling bin that fits in a cupboard. So they lug it out and they fight to do it because if they get a tick and the more ticks you get, the more pocket money you get at the end of the week so they fight over taking out the recycling. But it’s just one of those things that they just get. I think kids understand a lot more than we ever give them credit for and they seem to really understand the impact that we’re having on the planet. They just get it.

LEE:

Yeah and kids are idealistic because, and I think that’s a good thing that should be encouraged more in adults, because sometimes we lose sight of what would be ideal and tell ourselves it can’t be that way and therefore don’t act in a way that even helps us move towards what’s ideal. And so often I am conscious that kids who read this book, maybe the ones rousing on their parents actually when it comes to putting things into the bin and things like that, so I think kids are really good agents for change within their own families because we want to be on our best behaviour for those kids.

LAURA:

Yeah, we know we’re their role models. Speaking of kids again, and again my eldest son, he’s very perceptive on sustainability issues. I mean he’s interested in what I do and asks a lot of questions, but we were just walking to school last week and just out of nowhere he said, “Why are we still cutting down trees, Mum?” I was just like, “Well that’s a very good question.” Why the hell are we still cutting down trees? He’s like, “We know the impact of cutting down trees and yet,” … we ended up having this big discussion on, cause he’s like, “Trees give us the air that we breathe. Why are we doing that if we need that air to breathe?” And like, yeah, it is that basic. It is that simple. Why are we doing these actions on our planet that are impacting our own health?

LEE:

Absolutely, and I think when you start to talk about waste, you start to talk about consumption. So you’re talking about buying something that’s made from recycled paper versus new paper or toilet paper and things like that. You’re talking about how many times we can actually recycle paper and it’s still great, and we’re talking about whether something had to be mined from the ground or grown and we’re talking about whether something can be composted and tending to soil to grow something to eat or not. And so it does open up all these other things you can talk about as far as not just the decision you make when you’re holding something in your hand deciding which bin to put it in, but the decision you make when you’re shopping or when you’re nagging your parents for something that you want, what’s it made of? Where did those parts come from? How long is it gonna last? Could we get one secondhand? When you’re finished with this and you don’t want to play with it or wear it, can we give it to someone else? It opens up all these other discussions that are also really important, not just thinking about the end of life of a product, but the start as well.

What is the book about and how does it inspire an understanding of sustainability in our kids?

LEE:

So How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet is a garbological adventure. So what that means is as there’s a main character called Captain Garbology, so she loves the science of garbage, which is garbology.

LAURA:

Ooh, I love it. She’s a she.

LEE:

Oh yes. A lot of people don’t realise that. I realised when I get to the she part of the sentence that most people have already made an assumption that Captain Garbology is a he, but yeah, Captain Garbology, if you’ve bought this book or if you’re rating this book, you’ve actually signed up to Captain Garbology’s Waste Warrior Training Programme and you’re one of her new recruits. So Captain Garbology takes you as the reader through various stages of training and you get a badge of honour at the end of each stage, depends on how well you went that brings you closer and closer to becoming a waste warrior at the end just like each stage of the journey is where we’re exploring a different journey that our waste could go on. Whether it’s going to the landfill or the recycling sorting facility or into a food waste bin or what happens if our food goes to the landfill instead of this food waste bin? Are there other ways we can deal with waste or reuse and repurpose and repair things? So every stage goes through that. It kind of has the same structure.

So we start off with Captain Garbology also gives you the ability to shrink down to the size of your waste, a little bit Magic School Bus style. So you can actually dive in the bin with the main character and her two sidekicks who are to waste warriors in training and you get really up close to the garbage. There’s a lot of gory mess and bin juice and fart jokes and things. But it’s a bit of an adventures quest.

And then there’s always in each part there’s garbology 101 where are we going through what’s the basic of the garbage science of this part of our quest. And there’s always in each stage a hands on activity, so that’s a DIY activity just with every day materials, stuff in the recycling bin that students, kids any age can do to actually solidify some of those messages and have a lot of fun.

And then at the end there’s a little quiz and there’s a few activities throughout it. So once you’ve had a look at your quiz and you’ve gone through that stage, you get that badge and then you go onto the next stage of your Waste Warrior Training with Captain Garbology. So it’s kind of trying to gamify the process while making it a bit of an adventure so that there is a fictional element to it with the character. But there’s also really basic Garbology, and there’s a glossary at the back with any of those tricky sustainability words. So I didn’t want to shy away from using some of them because it’s really great to introduce new words at any age, but there is a definition there at the back in the glossary which is called the “grossary”. So yeah, that’s Captain Garbology.

But the illustrations, I love the illustration so much. James Hart is the illustrator and sometimes I’d just write in my draft like a little description of something I had in mind here. I’m thinking there’s a food waste feast and there’s all these microbes eating the food waste and it’s like a big feast. And he’d just take a look at the image he drawn, I’d just get it emailed to me and I was like, oh my God, that’s exactly what I had in mind and more. He’s just got so much fun and movement to the images. You could imagine how they’d be animated and I just loved the way he’s illustrated it as well.

LAURA:

I feel like that sounds great. I can’t wait to read it. Now I know it’s coming out on World Environment Day, June the fifth, that’s correct? How can our listeners get their paws on your book and secondly follow you in your work?

LEE:

Well, you’ll be able to buy it from World Environment Day, June 5th, in all good bookstores and it’s available online at Penguin. And the way you can follow me and my work and also there’s a link on all these social media pages of mine now to where you can do your online order. I have the same handle on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, it’s @constababble. So My name is Lee Constable and I’ve just turned it into Constababble, C-O-N-S-T-A-B-A-B-B-L-E and you should be able to find me and click on the link in my bio in any of those and that’ll take you to the page all about How to Save the Whole Stinkin’ Planet.

LAURA:

Fabulous! It’s great timing for World Environment Day. Everyone’s having the conversation right now, so let’s get it out there into families and into schools so we can all recruit the next wave of waste warriors to help save the whole stinking planet.

LEE:

That’s it. Cause at the end of the day, the whole point of this is it’s all about kids being heroes and them not just becoming waste warriors, but sharing what they’ve learned and really making an impact on the world in a way that makes them feel empowered.

LAURA:

Well, thanks so much, Lee, for coming on the podcast today to tell us about your book, but also have a great chat about science communication and what the arts can do for science and what science can do for the arts. It’s been fabulous to have you on the show.

LEE:

My absolute pleasure. Thanks so much for having me on the show.

- Sustainable Home Design- factors to consider to maximise sustainability - July 28, 2022

- Advantage and Disadvantages of Tiny Houses - May 31, 2022

- How School Strike 4 Climate is Empowering Youth to Fight for Their Future - May 1, 2022

Laura Trotta is one of Australia’s leading home sustainability experts. She has a Bachelor of Environmental Engineering, a Masters of Science (in Environmental Chemistry) and spent 11 years working as an environmental professional before creating her first online eco business, Sustainababy, in 2009. She has won numerous regional and national awards for her fresh and inspiring take on living an ‘ecoceptional’ life (including most recently winning the Brand South Australia Flinders University Education Award (2015) for the north-west region in SA and silver in the Eco-friendly category of the 2015 Ausmumpreneur Awards). With a regular segment on ABC Radio and with her work featured in publications like Nurture Parenting and My Child Magazine, Laura is an eco thought leader who’s not afraid to challenge the status quo. A passionate believer in addressing the small things to achieve big change, and protecting the planet in practical ways, Laura lives with her husband and two sons in outback South Australia.

Laura Trotta is one of Australia’s leading home sustainability experts. She has a Bachelor of Environmental Engineering, a Masters of Science (in Environmental Chemistry) and spent 11 years working as an environmental professional before creating her first online eco business, Sustainababy, in 2009. She has won numerous regional and national awards for her fresh and inspiring take on living an ‘ecoceptional’ life (including most recently winning the Brand South Australia Flinders University Education Award (2015) for the north-west region in SA and silver in the Eco-friendly category of the 2015 Ausmumpreneur Awards). With a regular segment on ABC Radio and with her work featured in publications like Nurture Parenting and My Child Magazine, Laura is an eco thought leader who’s not afraid to challenge the status quo. A passionate believer in addressing the small things to achieve big change, and protecting the planet in practical ways, Laura lives with her husband and two sons in outback South Australia.